Causing a Rackett

This article was originally published in Summer 2017 on my blog on Tumblr.com.

Starting this past semester I have been researching a short-lived musical instrument called the rackett. My goal is to recreate a consort of racketts, as well as explore organology through 3D-printing.

|

About the rackett

The rackett is a double-reeded instrument (much like the bassoon) that existed from the late-Renaissance through the early-Baroque periods. Although the country of origin is unknown, racketts are likely German or Italian creations; the name stems from the German work for “crooked:” rankett. The instrument’s convoluted design and quiet projection mostly likely resulted in its demise, lasting less than 50 years on the timeline. But history has not forgotten them. ➜ Listen to David Munrow and members of the Early Music Consort perform on Renaissance racketts (Youtube) |

|

The design

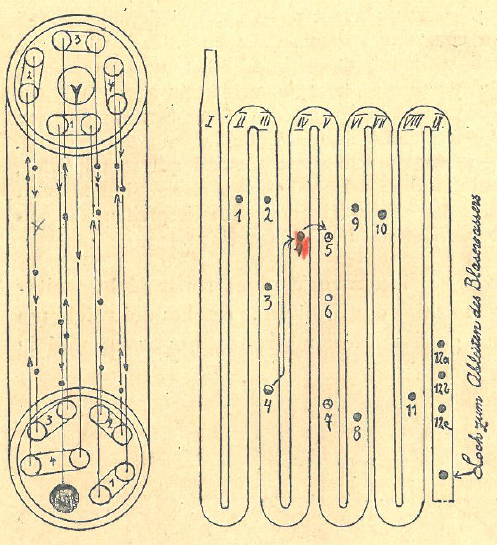

There are two types of rackett designs, the Renaissance and the Baroque. They differ in two ways. The Renaissance rackett is cylindrical bore, and uses a reed placed at the top with a pirouette. The Baroque design on the other hand is a composite conical bore (a series of ever growing, but not tapered cylindrical bores) and employs a bocal much like a bassoon’s. I will be focusing on the Renaissance design in my research. The rackett’s design is ingenious in a way; nine parallel bores are drilled into a cylinder and connected from alternatively top and bottom by carving through the end walls and sealing with cork plugs (Fig. 1). A double reed connects to the thin bores that run up and down the instrument, resulting in a deceivingly long instrument, and producing a low buzz. The discant rackett, smallest in the rackett family, is a 12 cm tall cylinder with a diameter of 4.8 cm. The small instrument packs over a meter of tubing (Fig. 2). |

|

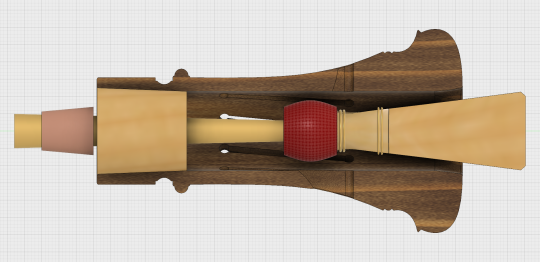

A pirouette is attached to the top of the instrument, from which half the reed protrudes (Fig. 4). The pirouette, in addition to being a very decorative part of the instrument, has a curious practical function. The rackett, being a low instrument, requires a very loose embouchure (lip pressure) in order to achieve low notes; too tight, and the instrument cannot reach the low notes. The problem with a loose embouchure on a free standing reed is that the player end up not having enough hold on the reed to keep it from sliding positions in the mouth. Thus a pirouette acts as a guard of sorts that the player’s mouth position can hold firm while maintaining a loose embouchure.

|

Racketts were made of boxwood or ivory; the only surviving originals (in Leipzig and Vienna) are made of the more durable ivory. The issue with racketts constructed from wood was the issue of moisture. The compact design of the instrument made it hard to wick out moisture. Consequently, cracks, rotting and even explosions were noted in the history books.

The sound

Because of the long tubing, the rackett family is a bass-y set of instruments. The discant rackett has a range of about G2 to D4. The tenor-alt, bass, and gross-bass (great bass) go even further down the bass range. Due to the small bore size however, (the discant’s bores are a mere 6mm in diameter) the instrument is considerable quieter than other reeded wind instruments (much like how the larger the bore of a tuba, the larger the sound, the small the bore, the quieter the sound). They emit a low buzzing timbre, much like the combination of a bassoon and a kazoo. Their unique timbre allows them to cut through large chamber ensembles.

➜ Compare the range and sound of a baroque contrabassoon and the great-bass rackett (Facebook, Unholy Rackett)

Because of the long tubing, the rackett family is a bass-y set of instruments. The discant rackett has a range of about G2 to D4. The tenor-alt, bass, and gross-bass (great bass) go even further down the bass range. Due to the small bore size however, (the discant’s bores are a mere 6mm in diameter) the instrument is considerable quieter than other reeded wind instruments (much like how the larger the bore of a tuba, the larger the sound, the small the bore, the quieter the sound). They emit a low buzzing timbre, much like the combination of a bassoon and a kazoo. Their unique timbre allows them to cut through large chamber ensembles.

➜ Compare the range and sound of a baroque contrabassoon and the great-bass rackett (Facebook, Unholy Rackett)

|

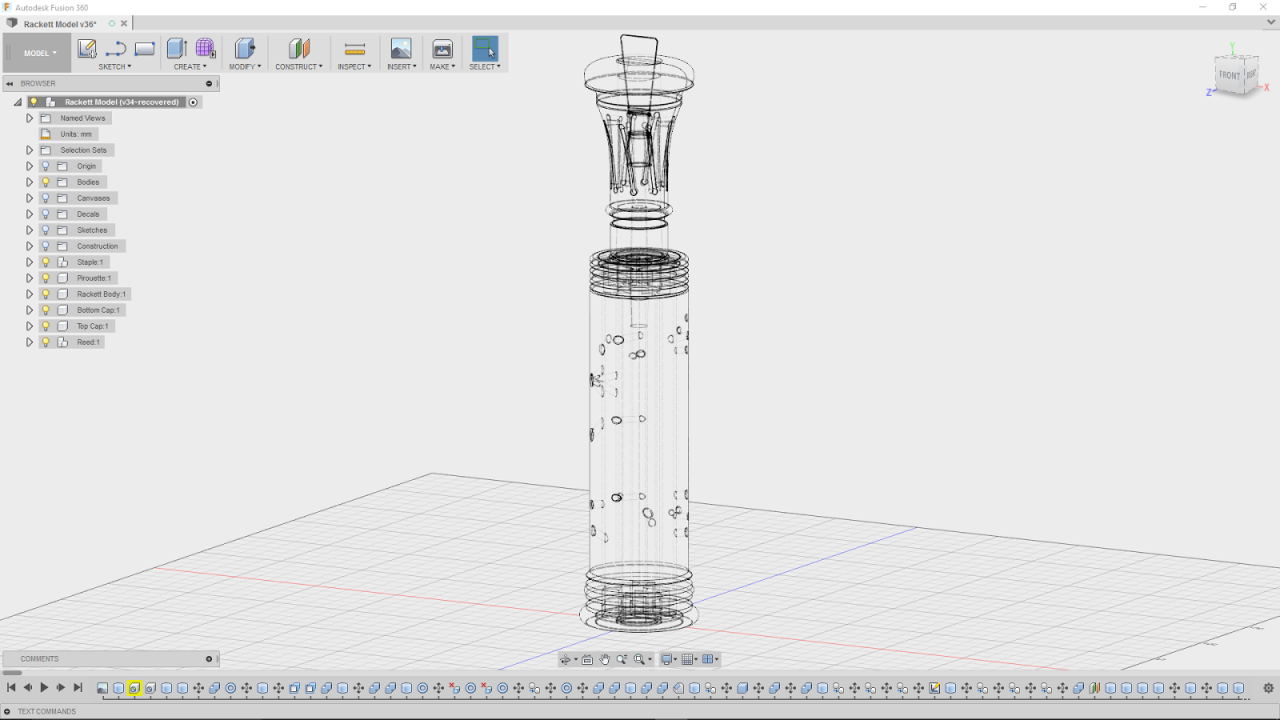

3D modeling

Following in the footsteps of Ricardo Simian and Jamie Savan and their work in 3D printing the Renaissance cornett, I decided to step up the game with a more complex instrument. I have been modeling using Autodesk Fusion 360 (See Fig. 4). I have spent the last six days creating a digital replication of a Renaissance tenor-alt rackett based on published blueprints from the Toronto Consort Workshop publication of rackett-building instructions. Their design is modeled on the Leipzig original. The first five days were spent creating the main model which consists of the body (main body, plugs, and end caps), the staple, the pirouette, and the reed (similar to a bassoon reed). The sixth day was spent redesigning the rackett for 3D printing. |

Preparing the 3D model for printing required changes to the design (I should note that all the parts, except the reed, will be 3D printed). As I will be using a Formlabs Form 1 SLA printer, I needed to adapt the model according to its restraints.

The Form 1 cannot print larger than a 125x125x165 mm object. Although the pirouette, staple, and reed are all separate from the body, and all much smaller than the maximum print size, the body itself is 200 mm long. To fix this, I basically chopped the rackett in two, combined the plugs and end caps with the body, and created a male-female design to minimize air leakage, especially from bore to another (Fig. 5). The advantage of this design, as far as I can tell, is that it will be easier for condensation to drip out of the instrument after use.

The Form 1 cannot print larger than a 125x125x165 mm object. Although the pirouette, staple, and reed are all separate from the body, and all much smaller than the maximum print size, the body itself is 200 mm long. To fix this, I basically chopped the rackett in two, combined the plugs and end caps with the body, and created a male-female design to minimize air leakage, especially from bore to another (Fig. 5). The advantage of this design, as far as I can tell, is that it will be easier for condensation to drip out of the instrument after use.

Hopefully, early into fall semester I can print this one out and give it a try! I’d like to print this in clear resin (Fig. 6); it’d either be really cool, or mildly cool and then eventually disgusting to look at.

This is merely the beginning of this project, however. I intend to continue to work on it through the entire 2017-2018 academic year, culminating in a research paper, lecture/presentation/demonstration, and a consort concert.

Thanks to: My project adviser Dr. Sarah Waltz, outgoing Powell Scholars Director Dr. Cynthia Wagner-Weick, the Powell Scholars Program, and the University of the Pacific. Also thanks to Gregor for introducing me to this monstrosity of an instrument.

Additional resources

Kite-Powell, Jeffery T. “Racket.” A Performer’s Guide to Renaissance Music. New York: Schirmer, 1994. 76-78. Print. A short but detailed profile of the rackett, as well as some pointers on playing the instrument.

Robinson, Trevor. “Racketts.” The Amateur Wind Instrument Maker. Amherst: U of Massachusetts, 1973. 71-75. Print. Robinson provides some basic information about the rackett, as well as a modified (in some ways simplified) rackett design accessible to hobbyists. The book includes blueprints and finger-hole measurements. Additionally, the rest of the book is an intriguing resource, covering several other instruments as well.

Kite-Powell, Jeffery T. “Racket.” A Performer’s Guide to Renaissance Music. New York: Schirmer, 1994. 76-78. Print. A short but detailed profile of the rackett, as well as some pointers on playing the instrument.

Robinson, Trevor. “Racketts.” The Amateur Wind Instrument Maker. Amherst: U of Massachusetts, 1973. 71-75. Print. Robinson provides some basic information about the rackett, as well as a modified (in some ways simplified) rackett design accessible to hobbyists. The book includes blueprints and finger-hole measurements. Additionally, the rest of the book is an intriguing resource, covering several other instruments as well.

EPILOGUE: I've had the pleasure of hearing from several people across the world,– including Italy, the UK, Sweden, and the US– asking about my research on the Renaissance rackett. Unfortunately, due to various reasons I did not continue my research on the topic. However, I am happy to continue sharing information as I learn about it, or share 3D files. –Jul. 2019